Notes on "Merch"

“Merch.”

The quintessential example of the Internet evolving and shaping language as we know it today. An abundance of definitions exist for this abbreviation, which emphasizes its distribution and how its rendering is contingent on context. Merchandise, by definition, is a good to be bought and sold, but merch is a complex word that lives more in our culture than it does in commerce.

Let’s take one graphic t-shirt out of your closet. Likely, you will own at least one, if not multiple. A Guns n’ Roses tee for the classic rock father? Perhaps a Hello Kitty top for the Japanese fashion and anime-obsessed teenager. Your old sorority printed on a front pocket, or the coffee shop you worked at in high school – the t-shirt still burrowed at the bottom of your dresser. A costly Supreme tee for the average hype-beast, or a Mumford & Sons graphic you picked up at your last trip to Bonnaroo.

Merch can entail all of the above. It is an act of branding a logo on apparel. While this is far from new, when exactly did merch become a cultural phenomenon that lives digitally rather than in brick and mortar stores like Hot Topic?

It still exists in both realms for now, from a Chanel intertwined C logo on couture (established in 1925, about a century ago) to a tie dye hoodie labeled “Dump Him” by podcast sensation “Call Her Daddy” on accompanying BarStool Shopify store (established in 2020, a few months ago). Yet, the latter is an example of the market bursting at the seams with DTC. Many Youtubers, influencers, or digital marketers have capitalized on their personal brand by plastering a logo on merch and selling it via eCommerce. Think David Dobrik, Tana Mongeau, or gaming sensation PewDiePie with their names on colored hoodies and t-shirts sold in the thousands.

DTC apparel at large is an expansive market worth billions of dollars. Merch, or branded merchandise, accounts for a large slice of that eCommerce pie.

Wearing a logo on apparel signifies a shift in consumerism from the high-end fashion house labels to the affordable DTC stores with coined phrases screen printed on sweatsuits. Consumers are drawn to merch because it allows them to access community and status, especially if they don’t have the coin to spend on a Balenciaga hoodie.

Unpacking the History of Branded Merch

The cultural phenomenon of merch stems from and into two directions: Internet culture, and high fashion culture. The latter has a long history that paved the way to contemporary logomania.

Logomania: Madness, Repeated.

Iconic fashion houses are the monoliths and Greek gods of our contemporary couture, and their trailblazing has surprisingly lent a hand in shaping merch as we see it today. The icons of Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Fendi, and Gucci have represented how just a simple logo can represent more than just a brand, but an entire community and culture.

Logos is a Greek word signifying logic and reason, and underlines how a symbol represents the values and idea of a company or brand. Into the 80s, 90s and 2000s, fashion logos were either repeated on apparel or bolded, making the center statement of the fashion piece the brand itself. This gave off the boisterous impression of status and wealth, and therefore exclusivity.

Think of the interlocking G’s on a white t-shirt: Gucci’s $590 infamous top worn by all the influencers in 2018. Or the repeated F’s on Fendi slides that go for almost $700 a pair. Even Burberry’s signature plaid has become an icon in and of itself, the logo becoming just the muted brown and red pattern.

Fashion houses throughout history were the first to do this, long before branded merch of today. Mission Magazine says, “European fashion houses have managed to maintain identifiable branding for decades now, symbols that are intrinsic to their very DNA.”

During the hip-hop counterculture movement of the 80s and 90s, the iconic “Dapper Dan” or designer Daniel Day, copied recognizable high fashion logos and screen printed them on his own designs. In an interview with The New York Times, Daniel Day speaks on the desire to acquire a high-end product:

“The symbolism associated with Gucci, for example, is actually symbolism transference...When I was growing up, if you had diamonds and furs, that gave you clout. So when the big fashion brands began to come out, I noticed how people gravitated toward them, and that what identified these brands was their logo. So I incorporated that symbol in a way that represented fashion as I see it. This symbol, when it’s incorporated in fashion in a certain way and reflected through a certain culture, has the same impact as diamonds and furs.”

The reappropriation of designer logos was therefore a way for Day to symbolize fashion and culture through his own lens. He dressed and styled a variety of early rappers in this time period, beginning the act of something great: reinventing the wheel in couture to reinforce counterculture in its essence. He dismantled the European power in fashion by reapplying it to hip hop culture.

The recent rise of high-end brand Off-White is the epitome of branding as an entire product and aesthetic itself. Designer and owner Virgil Abloh labels his various apparel pieces with quotation marked phrases, like a women’s tote bag that says “Sculpture” or a pair of riding boots labeled “For Riding.”

This continuation of re-application and redefining of logos set off the chain reaction for logomania, and later on, branded merch.

Which Came First: The Internet, or the Influencer?

Branding merch works similarly to logomania to identify the consumer with a certain community and sense of belonging. The wearer of a SoulCycle sports bra signifies that they are a member of the trendy cycling community, and have status as someone who values wellness and exercise. Or, consider Sunlife Organics, a Malibu-based smoothie shop franchise that has quickly climbed to a healthy celebrity hangout spot, where consumers can rep a “Be Here Now” hoodie for $80.

Perhaps branded merch of today has become an iconoclast to the fashion industry, mocking its use of logomania over the years. Or, it’s even reinventing the wheel in the age of the Internet.

Consider the past decade of the “Hype Beast” era. By a cultural definition, a hype beast is referred to as a consumer who seeks out high-end and exclusive pieces. Sneaker-heads, Supreme, and thrifting all exist under this umbrella.

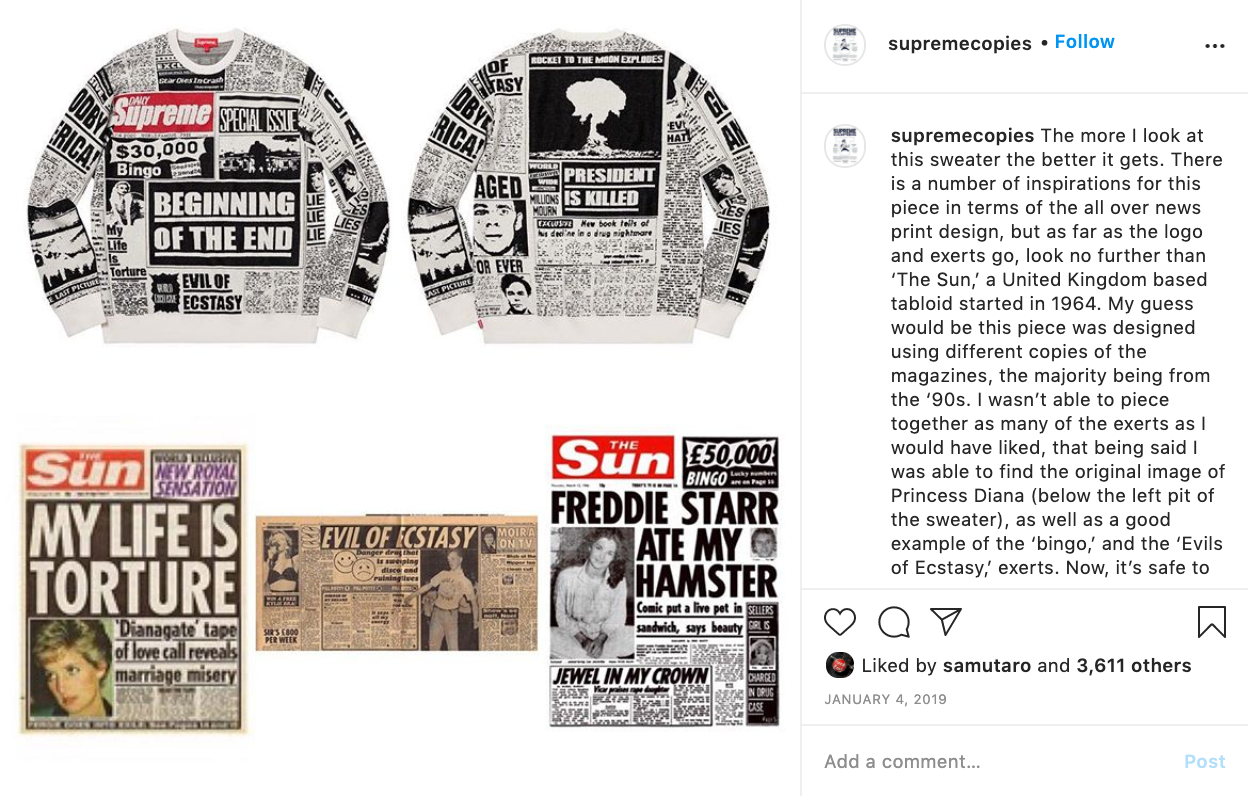

The brand Supreme is an example of how a logo transcends into an exclusive community and sets branding trends. The recognizable red block with white italicized text has been copied over and over, giving way to a repeatable model of branded merch. Ironically, Supreme builds its designs over copying other iconic or aesthetic logos in the commerce landscape. They’ve even borrowed from newspaper aesthetics or racing suits, transcending industry altogether. Life imitating art, and art imitating life.

Other higher-end brands like Kangol, Kith, or Bathing Ape show how the “hype-beast” world bridges the gap between the large demographic of fashion consumers and the high-end fashion. Their logos and branding are so identifiable, that wearers are walking billboards for the company.

Popular DTC brands today are emulating this branded merch model, whether they are aware of its historical implications or not.

DTC bikini brand Frankie’s Bikinis has been producing top-of-the-line women’s swimwear since 2012. In the past few years, owner and designer Francesca Aiello has extended into apparel, launching a line of pastel sweatsuits with “Frankie’s” printed on the chest. The brand has built a tight community, and quickly leapt from DTC to the runways of Miami Fashion Week. Another example of eCommerce having one foot in Internet culture, and the other in high-end couture.

Livin Cool is a Los Angeles based lifestyle DTC that sells colorful loungewear with a summer-inspired twist. Created by photographer Emaneule D’Angelo, he claims his brand is all about “photography, bright colors, comfortable clothing, and distinctive designs.” The product model is minimalistic: sweatsuit fits that come in colors of exclusive drops, with the appealing phrase, “Livin Cool,” on the chest.

The success of these DTC brands that build their aesthetic appeal on the art of branded merch is largely marketed by influencers. Supermodels Sofia Richie and Bella Hadid rock Livin Cool on their Instagrams, and Francesca Aiello is an Instagram influencer herself. For this reason, merch lives in a space of social media and digital celebrity that is a largely cultural phenomenon as well as a fashion evolution.

Contextually, we are witnessing the rise and perhaps peak of influencer marketing. According to GrandView Research, the global influencer marketing platform market size is valued at almost 6 billion USD today, and projected to grow to 23.25 billion USD by 2025. What’s helping it scale is “the rising need for brands and agencies to foster deeper connections with consumers.” The company's ticket to accessing a devout and relatable audience to promote their products are influencers.

With the Gen Z and millennial generations as the new wave of consumers, higher-end fashion brands are struggling to connect with them as their products feel out-of-touch and out-of-their-price-range. The Digital Marketing Institute claims that 70% of teens trust influencers more than traditional celebrities, which puts Tana Mongeau’s merch up to bat against Hailey Bieber rocking a Prada jacket. And, 86% of women use social media for purchasing advice, placing influencer marketing at the center of the consumer funnel, instead of the Vogue magazine at the nail salon. Women are likely scrolling through Instagram for shopping inspiration while getting their pedicure rather than flipping through a fashion magazine to browse designer ads.

Merching 101

The business model of merch is aggressively simple. Take a streetwear inspired silhouette, ensure it’s comfortable and soft, and plaster an aesthetically pleasing logo on it that is relatable and authentic to the brand or creator. What makes this model successful is how easily it can be repeated. Additionally, streetwear fashion has been integrated into ready-to-wear DTC companies. Comfortable sweat suits that you could wear to sleep but also out on the town go for anywhere between $50 to $200. Streetwear lives on runways, and the actual streets. With COVID-19 forcing consumers to stay inside, 2020 has seen a rise in apparel DTC turning to quality loungewear options.

The Internet has given birth to a marvel of branded merch, especially from the Youtube and social media communities. Youtubers or influencers launch merch to economically capitalize on their fan base. Fans or consumers are willing to buy and wear a brightly colored sweatshirt with their favorite phrase or influencer’s name on it. Not only is the aesthetic vigorously in-style, but it allows the consumer to access the exclusive community or fan-base.

Youtube sensation, Nelk Boys, are popular for their crude humour prank videos, which have gone viral on the platform many times over. Their merch shop, Full Send, hosts a variety of Gen-Z tailored phrases on apparel, and advertised by a comical display of bikini-clad girls and weight-lifting boys. Their fan base is likely a group of adolescent teens, which constitutes their merch consumers as well. The identifiable apparel allows for a community in their brand, which transcends just product into video entertainment.

Instagram influencer Emily Oberg launched a DTC titled Sporty & Rich, displaying how any eye-catching phrase can sell, contingent on branding. The streamlined athleisure wear boasts wellness phrases like “Drink Water” and “Athletic,” accessing a niche consumer base that lives on Instagram and values displays of health.

With the dreaded new “influencer” career path, some Youtubers and social media stars are not always advertisement-friendly. Consider an Instagrammer that built their following on weed-smoking, or a Youtuber demonetized on platforms for using profanity or paraphernalia. The solution is to make other revenue streams through merchandise.

Consider Youtuber Tana Mongeau, who is continuously front and center in tabloids for her raucous celebrity behavior. Usually demonetized on Youtube, she extended into merch, selling hoodies that say “Scandalous,” and therefore capitalizing on the very trait she is slandered for, and building a community of followers. Mongeau uses the platform FanJoy to create and distribute her merch. But FanJoy is only one of many platforms that offer these services.

Merching Services

This niche space of influencer marketing is really not so niche after all: there’s an entire market built on branding, design, and distribution for influencer or branded merch. Among some of the most popular platforms are Bonfire, Merchology, and Printify, that allow the creator to simply partner with the company to create and sell thousands of their branded merch pieces. Whether you’re an influencer selling your own brand, or a DTC company hoping to stick a toe into the merch pond, there are dozens of merchandising businesses to help create and distribute

Merch companies like MerchLabs are designed specifically for social influencers, or Icon, which is a collective focusing on quality and range of styles. Killer Merch handles full-service marketing as well as merchandising.

Kite is a full-service merchandising company that allows content creators to upload their designs and phrases to sell directly to their Shopify, with a plugin integration. Kite advertises their services as a way to acquire consumer data as well, so when a follower purchases a mug or tee-shirt, the brand has access to that consumer’s data to add them to a mailing list or marketing endeavor. Kite claims that, “Influencer merchandising is a fairly niche, unknown topic. But as word gets around how easy it is to monetise your online presence with zero-inventory merchandising, we expect that to change quickly.”

Beyond the influencer world, all kinds of businesses and organizations are harnessing the power of merch.

Mayfair Group is known as an Instagram-native DTC shop, selling female empowering sweatsuits with positive phrases. Yet, they are primarily a full-service branding agency, displaying how merch can blur the illusion of what a company is capable of.

The banking application Fast used branded merch as a marketing tool, spreading the word and building their brand identity up through the logo. Glossier was a forerunner in this tactic by selling pink sweatshirts with the white logo, as founder Emily Weiss envisioned far before the launch of the DTC makeup brand.

Glossier set up a precedent of a DTC product first, merch second. Recess, a canned CBD beverage company, sells a variety of hoodies, tees, socks, and slides with their whimsical and laid-back branding in warm colors. Onda, a sparkling tequila DTC brand, launched a line of baseball caps with a retro, surf-inspired font.

Perhaps branded merch is tackling the issue of product glass ceilings in DTC brands. Good apparel is not hard to come by, as long as you are drawn to a company’s brand identity. The art of branding and merchandising is similar to the art of the meme on social media: adapting and evolving the existing framework to fit the brand’s context instead of directly emulating the established model.

Are Collaborations Breaking Down the Wall?

With consumers drawn to branded apparel, how can high-end fashion couture take some advice from this DTC native strategy? Logos are clearly everything to draw eyes, and collaborations between brand and artist or brand to brand are breaking down this wall.

Jonathan Chueng of Levi’s says, “Collaborations help us stay close to the centre of culture.”

The recent drop of Cole Haans sneakers, partnering with the communication software company Slack, is an example of how established designers want to enter an Internet culture, while keeping their literal feet in the traditional fashion world. Hermes recently did an Apple Watch collaboration to enter the tech industry as well and broaden their consumer base to reach younger audiences.

Pop star Justin Bieber collaborated with Crocs footwear, a notoriously nerdy rubber clog, to make a fashionable yellow pair labeled with his streetwear brand “Drew.” As an Instagram savvy celebrity, Justin Bieber could single-handedly make Crocs cool again, showing that it doesn’t necessarily take a rebranding to reach an audience, just the right influencer partnership.

Regardless, the intersection of DTC and high fashion is ruled by the concept of merch, and the way the two spheres interact says everything about a new wave of consumers and brand building. Modern Retail writes how brands are increasingly leaning on merch, because it is “marketing that makes money.” With the right product-market fit, any brand, whether young or old, can bolster their identity, build an exclusive community, and access an Internet culture that is transparent and porous across industry through the art of merch.